Welcome back to the third installment of my weirdly complicated journey through WebGL. Today I’ll treat you to actually using the setup from last week’s article to draw some shapes. Read the previous article here.

Setting up State

With the distinction between engine and rendering engine from last week’s article, an understanding of the rendering pipeline, and a simple program at hand, we can finally get to drawing things!

To recap, what we want to achieve is an iris look, and we need to use triangles for that. So let’s do that.

Essentially, what we want is to represent a single ray by a single triangle, and simply instantiate as many rays as we want. However, we will also need to remember some state because we do have to move these rays at some point.

How can we represent a triangle, though? Well, the easy answer would be: three coordinates. But we shouldn’t do this, for two reasons: First, I want to animate those rays at some point. And second, we can make use of circle math for that.

Here’s the first part of circle math coming in. Since we want to draw an iris, we have a bunch of rays arranged in a circle, and instead of using coordinates to describe them, we can also describe them by providing an angle and a radius. So instead of remembering six coordinates, we can only store two numbers.

To make working with the data structure simpler, let’s set up a simple interface (if you’re sticking to plain JavaScript, you won’t need this):

interface Ray {

radians: number,

width: number,

radius: {

inner: number;

min: number;

max: number;

current: number;

inc: boolean;

}

}

Here, we remember a few additional pieces of data that we will only need for the animation. Effectively, what we need is only the radians, which describes where on the unit circle this triangle will be; the width which describes how “thick” the triangle will be (where width is provided in radians, too); and the inner and outer (“max”) radius. We supply an inner radius because we don’t want the rays to start at the center. This way, we can make the rays form a circle at their center, which symbolizes the center of the eye. Furthermore, by saving the radius individually for each ray, we can vary that and make the rays vary in size. The other properties will be used in the animation later.

Now, we need to create a few rays. Here’s the function that does this in the IrisIndicator class:

function generateRays () {

this.rays = []

const { cWidth, cHeight } = this.engine.textureSize()

const canvasDiameter = Math.min(cWidth, cHeight)

const canvasRadius = canvasDiameter / 2

const outerRadius = 1.0 * canvasRadius

const innerRadius = 0.3 * canvasRadius

const minVaryRadius = 0.6 * canvasRadius

const overlapFactor = 3 // Should be > 1

const widthInRadians = ((2 * Math.PI) / (this.nRays * 3)) * overlapFactor

for (let i = 0; i < this.nRays; i++) {

const pos = i / this.nRays

const centerInRad = pos * 2 * Math.PI

const RADIUS_VARIATION = 0.1

const rMin = minVaryRadius + Math.random() * RADIUS_VARIATION * canvasRadius

const rMax = outerRadius - Math.random() * RADIUS_VARIATION * canvasRadius

const startRadius = minVaryRadius + (rMax - rMin) * Math.random()

this.rays.push({

radians: centerInRad, width: widthInRadians,

radius : { inner: innerRadius, min: rMin, max: rMax, current: startRadius, inc: Math.random() > 0.5 }

})

}

}

Aside from the circle math, this code should be fairly straight forward. A few notes: First, we calculate positions based on the actual size of the canvas (which is returned by the textureSize method which will be introduced later). Second, we allow the amount of rays to vary. Experimenting with that number I have found that, the larger the canvas becomes, the more rays are necessary to retain that “iris” resemblance. Too few, and it looks like a comic star; too many, and it tanks performance. (I would have never thought that rendering a few triangles would actually be able to make my M2 Pro struggle, but here we are.)

Next, there is an “overlap factor.” What exactly is this? Well, we want the rays to not be discernible as the triangles that they are. For this, we need to overlap them a bit. This will make the end of one triangle to overlap with the beginning of the next one. That factor as well is entirely arbitrary, and I have found a factor of 3 to look quite decent. (If you make that factor too big, things will start to look weird.)

With this information at hand, we can quickly write a small function that takes in this circle information and spits out a set of coordinates for that triangle:

function coordsForRay (radians: number, width: number, innerRadius: number, outerRadius: number) {

const [rad1, rad2, rad3] = [radians - width, radians, radians + width]

const [

x1, y1, x2, y2, x3, y3

] = [

Math.cos(rad1) * innerRadius, Math.sin(rad1) * innerRadius,

Math.cos(rad2) * outerRadius, Math.sin(rad2) * outerRadius,

Math.cos(rad3) * innerRadius, Math.sin(rad3) * innerRadius

]

return [ x1, y1, x2, y2, x3, y3 ]

}

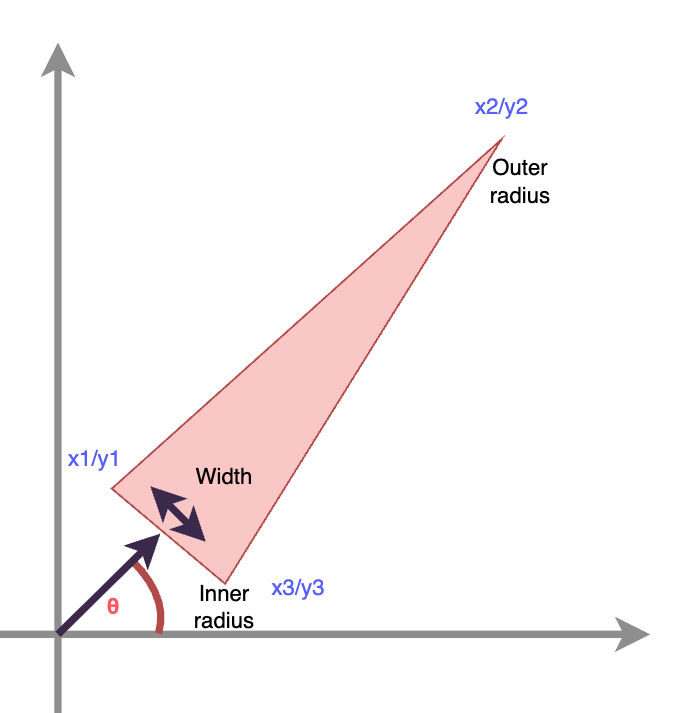

This should make intuitive sense: We have a center position and an offset for the two base-coordinates, and we simply calculate a position based on sine and cosine according to circle math. We then multiply these values (which are bound to $[0; 1]$) by the actual radius length, and we have three coordinates, centered around radians with the base being spaced width radians away from that.

(Nota bene: I could also have removed the dependency on the actual canvas size in this calculation of coordinates, and instead provided a scaling matrix later, but that’s an optimization that is simply not necessary for this simple animation, so I kept this code. Believe me, we’re not even 10% of the way to the final animation.)

Here’s a visualization of that:

Preparing the Shaders

At this point, we have some data available that we can draw. But how do we do that? Now we need to head back into the rendering engine and prepare it for actually taking in the data. This is something where OpenGL just provides a “default” way to do so. Remember from above that we have defined a variable in the vertex shader:

in vec2 a_position;

The in keyword tells OpenGL that this variable receives vertex data, vec2 just mentions that there will be two floating point values that comprise each position (one $x$ and one $y$ coordinate). What you have to do is provide OpenGL with all coordinates that need to be processed, and it will make sure to run the vertex shader with each of them.

To pass the data to OpenGL, we have to perform three steps:

- Create a vertex buffer

- Find the location of that vertex buffer in the vertex shader

- Bind that buffer

- Mark the buffer as being used to transfer vertex information

- Tell OpenGL what the data format is that you will write into that

Creating the vertex buffer is comparatively simple:

this.positionBuffer = gl.createBuffer()

We also need to tell OpenGL that whatever we will be putting into this buffer should be passed in as the a_position variable into the vertex shader. For this, we essentially have to “find” the memory location of that variable in the compiled program. We also need to do that with the u_resolution parameter that we use to tell the vertex shader what actual canvas resolution we will be basing the (absolute) coordinates on:

this.positionAttributeLocation = gl.getAttribLocation(this.program, 'a_position')

this.resolutionUniformLocation = gl.getUniformLocation(this.program, 'u_resolution')

Next, we tell OpenGL the data format that we will put into it:

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, this.positionBuffer)

gl.enableVertexAttribArray(this.positionAttributeLocation)

gl.vertexAttribPointer(this.positionAttributeLocation, 2, gl.FLOAT, false, 0, 0)

One thing to always remember in OpenGL is that, before you do anything with any data structure, you usually need to “bind” it, which essentially makes it active. This runs a bit counter to how JavaScript typically works, so it takes some getting used to. What we do above is (1) tell OpenGL to make the position vertex buffer active; (2) tell it that this buffer will be used to provided vertices to the shaders; (3) tell OpenGL the data format that we will provide the coordinates in (two floating point values, that is x/y coordinates).

Again, these functions are all separate, because for more complex applications you might want to re-use buffers to provide various types of data in various shapes, or maybe even write the same buffer into multiple locations.

Drawing Things

Now we have everything in place to finally draw something! Just as a notice: Zettlr tells me that we’re now at slightly above 4,700 words (since the beginning of the first article), and only now can we actually produce something. Everything before now was just the setup!

To draw something, let us quickly mock up a draw function:

class IrisIndicator {

// ... other code

private drawFrame () {

const data = this.rays

.map(({ radians, width, radius }) => {

return coordsForRay(radians, width, radius.inner, radius.current)

})

.flatMap(coords => coords)

const componentsPerTri = 3

const triangleData = new Float32Array(data)

const nComponents = componentsPerTri * this.rays.length

this.engine.draw(triangleData, nComponents)

}

}

And in the engine:

class WebGLEngine {

// ... other code

draw (triangleData: Float32Array, count: number) {

const gl = this.gl

resizeCanvasToDisplaySize(gl.canvas as HTMLCanvasElement)

gl.bindFramebuffer(gl.FRAMEBUFFER, fbo)

gl.viewport(0, 0, gl.canvas.clientWidth, gl.canvas.clientHeight)

gl.uniform2f(this.resolutionUniformLocation, gl.canvas.clientWidth, gl.canvas.clientHeight)

gl.clear(gl.COLOR_BUFFER_BIT)

gl.bufferData(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, triangleData, gl.DYNAMIC_DRAW)

gl.drawArrays(gl.TRIANGLES, 0, count)

}

}

And, finally, because we do not yet provide any textures or something to the fragment shader, simply make it produce the same color for all pixels that are rendered:

fragColor = vec4(0.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0);

This is simply a cyan color so that we can actually see the triangles when they are rendered.

That’s a lot of code. What the IrisIndicator class does is simply take our generated rays, produce coordinates for them, turn them into a one-dimensional floating point array, and calculate how many components are in the array. The latter just tells OpenGL that it should process this vertex information by taking two consecutive numbers, one after another. We have to do this, because this just makes the memory layout simpler and the operations faster.

We then pass this prepared information to the engine, which handles the drawing. First, we need to ensure that the display size equals the canvas size (this is a utility function courtesy of WebGLFundamentals). Second, we need to tell OpenGL that we wish to write to the canvas. We do so by setting the current frame buffer to null. (In OpenGL, we can also write to other frame buffers, for example if we want to do something else to the colors, like post-processing.) Third, we have to ensure that the viewport is set accurately.

The viewport simply tells OpenGL how to rasterize (i.e., how large the frame buffer actually is). While we’re at it, we also set the resolution variable so that the vertex shader can turn our absolute ray coordinates into clip-space coordinates. Fourth, we have to clear the canvas. (We need to provide a color, by calling gl.clearColor(r, g, b, a).) If we don’t clear the canvas, we’re only overwriting some pixels, which can lead to funny results (try it out!). I set the clear color in the setup code to a charcoal-gray-ish color:

const BACKGROUND_COLOR = [0.3, 0.3, 0.4, 1.0]

The last two lines finally actually do the drawing. bufferData writes the provided triangle coordinates into the positionBuffer, and drawArrays commences the actual draw. Only that final line really starts up the vertex shader and does all the calculating. One note of caution, however: You need to make sure to bind the position buffer properly. If you don’t, then OpenGL doesn’t know where it should write the data to. This line is missing here, because we bind the buffer above, and never unbind it. This is why I only kept a single vertex buffer: This just makes it easy, and avoids me having to remember that I need to properly bind and unbind the buffer.

(Nota bene: The binding and unbinding especially of textures was my most common error source, because it’s extremely easy to get confused which texture is currently bound, and if you try to write to a texture that is also bound to be read from, OpenGL will make funny noises.)

To actually run all of this, make sure to retrieve a canvas and the WebGL2 context, then instantiate a new IrisIndicator(gl), and finally call .drawFrame() on it.

At this point, you should be able to see some cyan rays displayed on your canvas!

Final Thoughts

That took an awful lot of code just to draw a bunch of small triangles onto the screen. When I was at this point, I think I was already en route to my New Year’s holiday, so past Christmas. It dawned upon me that I may have grossly underestimated the amount of work necessary to get all of this done.

But, alas, I did start, and I did produce something, so the sunken-cost fallacy started to keep me afloat for the remainder of this odyssey. Make sure to come back next week, where I will explain how I animated all of this. I’ll also explain how to actually render in sync with your display to avoid flickering. So stay tuned!

The Full WebGL Series

Jump directly to an article that piques your interest.